Barbara Clarenz at AtkinsRéalis explores how human centred architecture translates care strategy into lived experience, creating supported housing that feels genuinely like home – not only for residents but also staff.

Does it feel like home? That question guided a supported living project in Horley, Surrey, from my first visit to the former library site through to the first residents moving in.

It sounds simple, but it is a demanding test. ‘Home’ is not a checklist or a regulatory threshold; it is a lived condition. It is independence that feels natural, privacy that does not need defending, and access to community without obligation. Critically it must work for the people who live there, and the people who provide care. When either is compromised, the sense of home quickly disappears.

However despite good intentions, too much specialist housing falls short of this test. It may be compliant but it can feel clinical, accessible yet isolating, technically competent, but emotionally thin.

Sustainability is often treated in the same way – in the sense that it is measured, reported, but not always felt. For architects, the real challenge lies in translating care strategy into places that support everyday life with dignity, clarity and ease.

Designing independence without isolation

Supported independent living sits at a careful balance point between autonomy and care. Push too far towards independence and residents can feel cut off; lean too hard into support and daily life begins to feel supervised.

The brief for Horley, part of Surrey County Council’s Supported Independent Living Programme, was explicit: enable adults with learning disabilities and autistic people to live independently, within their local community, supported in a way that feels proportionate and respectful.

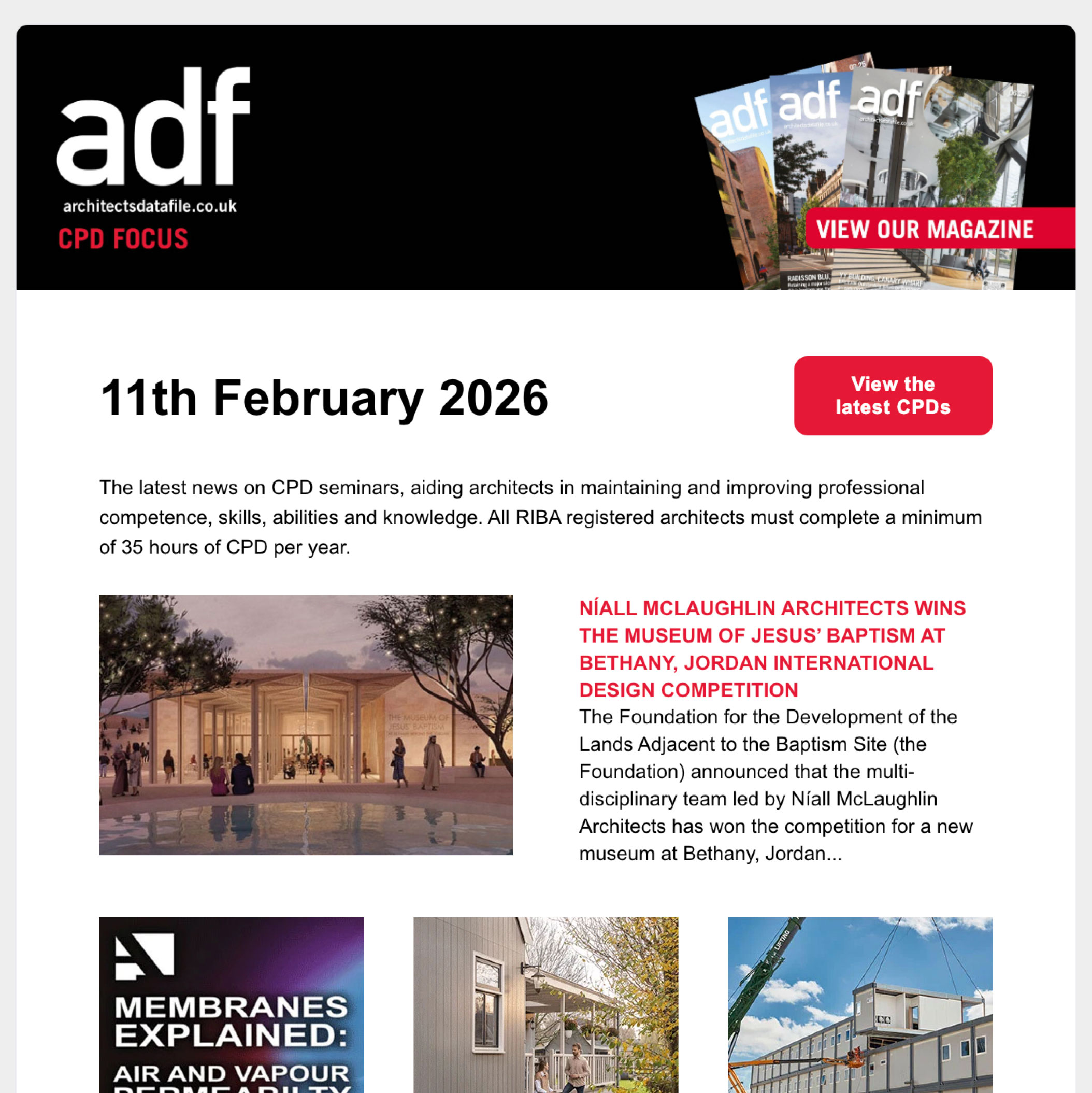

The response was architectural rather than symbolic. Horley was conceived as a small, legible neighbourhood rather than a single facility disguised as housing. Front doors are clear and recognisable, buildings are domestic in scale. Privacy is the default condition, with sociability offered by choice rather than design pressure.

This thinking led to two complementary residential typologies. A compact apartment building provides six self-contained homes for residents seeking maximum autonomy, each dual aspect with a private balcony or ground floor terrace.

Alongside this, two shared townhouses offer five ensuite bedrooms each, arranged around a generous kitchen and living spaces where shared life emerges naturally. Both layouts are calm and intuitive, reducing cognitive load and supporting confidence in daily routines. Variety is not an add on here, but is fundamental to dignity.

Making care environments work in practice

An environment that feels like home must also enable care to function smoothly. At Horley, architecture was developed in close collaboration with Surrey’s Adult Social Care team, occupational therapists, operators and specialists. Lived experience shaped the brief, particularly the small spatial frictions that can erode wellbeing over time such as glare across dining tables, echoing rooms, corridors that feel over exposed or confusing.

As such the design responses were deliberately straightforward, ensuring circulation is clear and concise, daylight is generous but controlled, acoustic separation is planned in, not retrofitted. It was important that staff routes keep support close without becoming visually dominant, ensuring help is always available while independence remains the foreground experience.

Operational clarity was treated as a form of care in itself which means storage is appropriately sized and logically placed in order to reduce clutter and unnecessary movement.

Sightlines allow supervision where required, without slipping into surveillance. Durable, low maintenance materials were selected to ensure the buildings retain their dignity over time because when environments reduce friction, staff wellbeing improves and the service operates with greater consistency and calm.

Predictability, choice & emotional safety

For neurodiverse residents in particular, belonging is closely tied to predictability so environments that are visually noisy, behaviourally ambiguous or overly stimulating can undermine confidence and independence, even when provision is well intentioned.

At Horley, careful attention was given to emotional legibility, looking at how a space is read, understood and trusted over time. This included consistent material palettes, clear thresholds between private and shared areas, and layouts that avoid unnecessary decision making.

Critically, choice is embedded at multiple scales so that residents can choose when to engage, where to retreat, and how visible they wish to be within the community. This might be as small as selecting a quieter route through the site or as significant as choosing between an apartment or shared house setting.

Architecture here does not prescribe behaviour but supports personal agency. Staff benefit too, working in spaces where boundaries are clear and everyday interactions feel calm rather

than reactive.

Safety, in this context, is not about control but reassurance. Robust detailing, good sightlines and passive supervision enable support to be discreet and responsive. Over time, this consistency builds trust between residents, staff and place. When people feel safe without feeling managed, independence becomes sustainable, and belonging stops being an aspiration and becomes an everyday condition.

Sustainability as lived experience

Sustainability at Horley was approached as something people would feel rather than simply measure. The scheme follows a fabric first, all electric strategy aligned with LETI climate emergency principles, supporting net zero readiness. Photovoltaic panels provide onsite renewable energy, while orientation and passive measures help maintain comfortable internal conditions without unnecessary complexity.

Landscape plays a central role in this lived sustainability. A gentle loop walk supports predictable movement for instance, pergolas provide shaded places to pause and allotment planters enable shared, purposeful activity.

Over time, layered planting softens boundaries between communal, semi private and private spaces, allowing residents to choose how they engage with nature and with one another. For residents and staff alike, sustainability is experienced through stable temperatures, fresh air, access to green space and lower energy costs.

The value created at Horley is shared as residents benefit from choice over privacy, sociability and routine, supported by spaces that are calm, legible and ordinary in the best sense. Staff work in an environment that supports the complexity of care rather than adding to it. Operators gain buildings that are robust, efficient to run and aligned with long term care and climate objectives.

Post occupancy evaluation and ongoing feedback will be essential, allowing the environment to evolve alongside the service. Small, informed adjustments can make a significant difference when learning is part of the design process.

So, does it feel like home? If that question continues to guide decision making, care strategy becomes place, and place becomes opportunity. The Horley scheme demonstrates that specialist housing can be safe, sustainable and operationally clear, while still feeling genuinely lived in, warm, and free.

Barbara Clarenz is head of residential London and the South East at AtkinsRéalis